Techniques

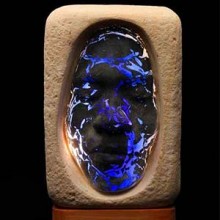

Silica, glass, pigments, Fusion... Infinite journey in the transparency and depth of color... Lights of matter united by FUSING.

The glass is also human companion

In its change from silica to the shimmering purity of the finished work in glass, sand dust becomes light. This is the talent and the art of Régis Granville.

Glass is also companion to man. Glass is purity and depth. Its firing, its fusion is alchemy. Polishing brings out its beauty and gives the work its meaning. Bubbles of air are the sparkle of life. Régis works on flat glass fused into multiple layers with inclusion pigments.

Humanity, Love, Gratitude, Joy, Peace Courage, Light…

Let's close our eyes, Caress the softness or the graininess of the skins of the glass, Let's touch to listen and find who we are.

Because art has this power to unite the hearts of men with depth. This is the invitation from Régis Granville

Fusing:

This is a technique already in use over 3,500 years ago for making objects in worked glass. Fusing is in fact one of the oldest techniques of working with glass. "To fuse" means to melt glass.

The United States was the first country to commercialize a complete range of compatible glass. Their know-how was disseminated widely and the English word "fusing" was generally adopted, thus overshadowing the French contribution to the rediscovery of this technique.

The fusing technique consists in stacking several layers of glass one on the other and fusing them in an electric kiln at high temperature, up to around 820o. After firing, these layers of glass form a thicker, homogenous layer with the various elements included. In principle, this process may seem fairly simple, but to be able to fuse glass satisfactorily, so that results are constant and durable, you must have appropriate equipment, a good knowledge of materials and techniques as well as sufficient mastery of a certain number of special operations.

Producing glass objects in a kiln used to be a long, complex process, which did not allow production of large format articles. The earliest period when this technique was widespread was in Mesopotamia, reaching its peak in Egyptian culture. At the beginning of the Christian era, the use of kiln-made glass was replaced by glass-blowing.

Glass worked in the kiln reappeared in Europe in about 1870. Since 1980 the technique has spread to the United States and subsequently throughout the world.

The glass used must have the same coefficient of expansion.

Layers of glass cannot fuse unless they are compatible.

The difficulty is to eliminate the molecular tensions in the glass during the cooling process, as each type of glass has its own coefficient of expansion. (Float glass: coefficient of expansion - between 0o and 300o C = 9.10-6. Wasser and Bullseye glass: coefficient of expansion - 90o C.)

Thermoforming:

Heat transforms glass by softening it. The material can then take the shape of moulds. It is possible to practise fusion and thermoforming at the same time, but this is not recommended if one wants to keep the whole design, which could become distorted. Glass begins to deform significantly at around 500o to 600o. Nevertheless, the heat cycles for thermoforming are in general shorter than fusion cycles, the maximum temperature being usually less than 700o.

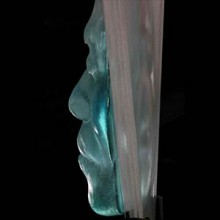

Glass paste:

Pâte de verre (glass paste) appeared at the same time as fused glass. By this method objects are made from fragments of glass which are melted in a mould. To show pâte de verre to advantage, the surface should be polished to show up effects of colour and materials together with the small bubbles left by air trapped among the fragments during firing. The technique for reducing bubbles is to extend the plateau of the firing curve when the temperature is at its maximum.